Edu 3: Post Debt Ceiling,TGA, Liquidity & MMF

After the debt ceiling deal, all eyes onto rebuilding of the TGA...

Unsurprisingly, the US debt ceiling deal got passed and with this legislation, the statutory limit on federal borrowing will be suspended until Jan. 1, 2025.

Here comes the interesting part. What happens after the debt ceiling is raised?

It will be the rebuilding of the Treasury General Account (TGA) at the Fed. And for the next following weeks, we probably be bombarded with the “reducing liquidity’ narrative by financial commentators/ media outlets. The story will go like this: the Treasury will be required to rebuild its TGA post-debt ceiling deal, so it issues bonds and drains liquidity out of the system, causing risk assets plummets.

But is this really the case?

Before delving into my perspective, let’s try to understand the thinking behind consensus and explore the mechanics behind the TGA rebuilding.

Scenario 1: Treasury issues bond to fund deficit spending

In this scenario, we are looking at when the government issues bond to fund deficit spending, but banks’ reserves (i.e. liquidity) will not be drained from the banking system.

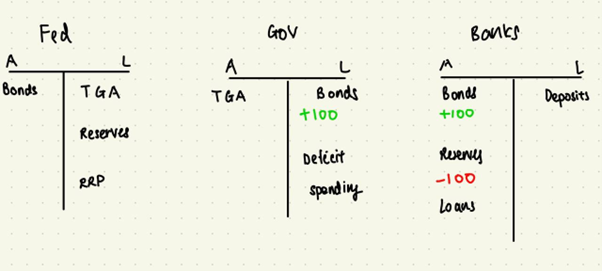

Assuming it is in equilibrium and banks operate in the traditional sense (i.e. Not the wholesale model we discussed in the education pieces) This is what the initial balance sheet looks like.

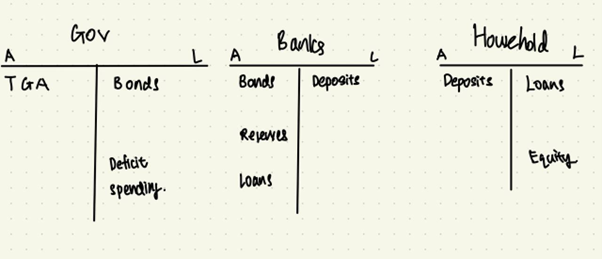

Fig 1: Initial Balance sheet (Chet Wee)

The government has to issue $100 bonds to fund the deficit spending. Banks have to absorb these bonds by using their reserves balances.

Fig 2: Post-Balance Sheet (Chet Wee)

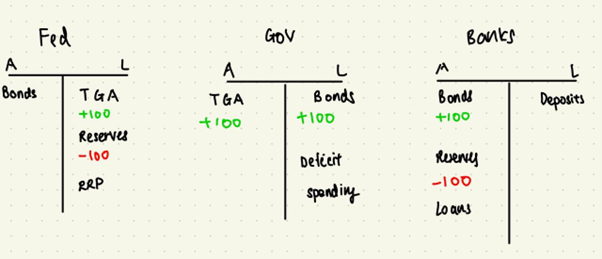

I know that the government balance sheet does not balance as of now, but we will balance it in a minute. Now the government engages in deficit spending and sends pay checks to households, thereby increasing their equity. The households then park the additional money into checkable deposits at the bank. Note that we assume that households do not hold currency (which is a realistic assumption Imo. Can you even find $10k sitting in cold hard cash in your apartment? Probably not)

With the increased deposits, the banks can refill their reserve balance.

Fig 3: Ending Balance Sheet (Chet Wee)

In essence, there is no reduction in bank reserves when the government issues bond to ‘’fund’’ deficit spending.

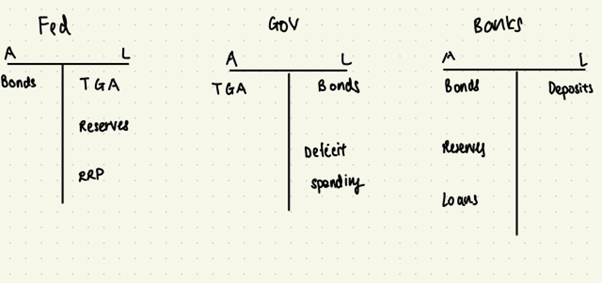

Scenario 2: Treasury issues bonds to rebuild TGA

But what about the scenario where the treasury issues bonds solely for the purpose of refilling its TGA account at the fed, post-debt ceiling?

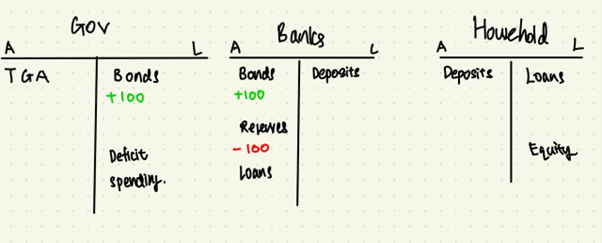

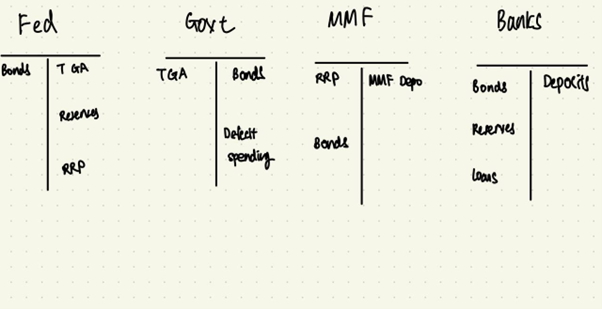

This is the initial balance sheet.

Fig 4: Initial Balance Sheet (Chet Wee)

The government issues bonds and the banking system have to absorb them by tapping on the reserve balances.

Fig 5: Post Balance Sheet (Chet Wee)

Likewise, we will balance it out in a minute. Now, the reserves from the reserve account at the Fed to the TGA account. As a result, there’s a rotation on the liability side of the Fed.

Fig 6: End Balance Sheet (Chet Wee)

As we can see, the TGA rebuild drains reserves from the system which is what the media outlet will paint. In this scenario, in the absence of any deficit spending on households, the banking system takes the brunt of the impact, by reducing its reserves balance.

Scenario 3: Treasury issues bond to rebuild TGA but absorbed by MMFs

However, Imo reality is more nuanced with the addition of the MMFs. In a nutshell, if the issuance of the bonds is absorbed by the MMFs, the banking system need not experience a decrease in reserves.

It’s a bit complicated but I will try to explain it.

To visualize it, we will too use the T-accounting of the balance sheet that we used earlier in the 2 scenarios.

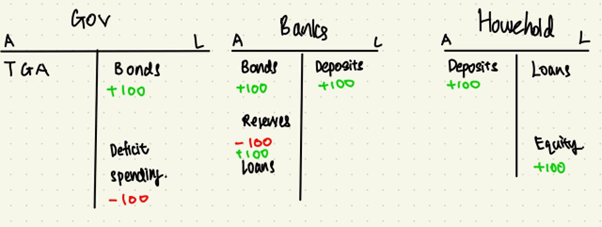

This is the initial balance sheet.

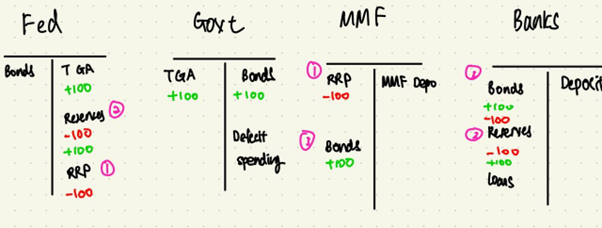

Fig 7: Initial Balance Sheet (Chet Wee)

The government issues bonds to rebuild its TGA. This issuance is absorbed by the banking sector via its reserve balances.

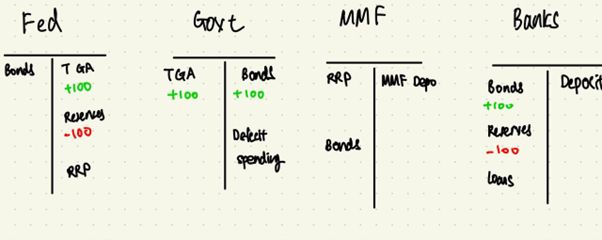

Fig 8: Post Balance Sheet (Chet Wee)

Now, we have the new actor – Money Market Funds (MMF), that is willing to absorb the bonds. Hence it draws down its Reverse Repo Facility (RRP) account at the Fed.

This is where it gets confusing.

In the first step, there’s an RRP drawdown on the MMF’s asset side and Fed’s Liability side to facilitate the purchase of these bonds from the dealer banks.

In the second step, this drain in RRP releases bank reserves into the financial system. Alternatively, one can think, of money rotating out of the RRP (MMF’s bank account at the Fed) into the reserves (Bank’s bank account at the Fed).

In the third step, bonds are shifted from the bank’s portfolio to the MMF assets.

Fig 9: End Balance Sheet (Chet Wee)

In a nutshell, if MMFs are willing to absorb the bond issuance of the treasury, there will not be a huge decrease in bank reserves from the banking system.

Note: If still confused about the mechanics behind the TGA, please attempt to just draw it out.

Back to the topic, one may ask why would the MMFs be willing to absorb the issuance of the bonds. Well, to be precise, they will be absorbing the T-bill issuance and not the longer-dated bonds (i.e. 5,10,30 years).

This is because of the MMFs mandate – to invest in highly, safe liquid short-term securities. They are more concerned with capital preservation than capital accumulation (i.e. they are very risk-averse), hence they do not want to be exposed to longer-tenor securities with the inherent duration risks.

On top of MMFs, we have institutional cash managers with trillions of dollars to invest in T-bills. This is because T-bill is analogous to money that pays interest. They are not willing to park large sums of money at commercial banks as they are exposed to the inherent credit risk (be it overnight or not) as FDIC insurance only covers up to $250’000 which are peanuts compared to the size of their assets.

Hence, holding T-bills (liability of the government) is better than holding deposits at a commercial bank (liability of the bank).

On the supply side, we have the treasury. Why are they more inclined to issue bills than bonds? This is once again due to their mandates. The composition of treasuries being issued is determined by the office of debt management which has 2 guidelines.

1) Regular and predictable issuance of treasuries (to help build investor confidence).

If the issuance of treasuries is so volatile (i.e. issuance varies so widely and due to supply forces, the bond prices keep jumping around), investors might not want to have them in their portfolio.

2) Lowest cost of funding

However, the T-bill issuance is not really restricted by the 1st guideline as they are very short tenor and have higher demand, hence the issuance of bills are not really stable. In 2020, to fund the Covid-spending, US$2T of T-bills were issued, dwarfing the issuance of bonds further down the curve.

It is expected that the treasury will issue roughly US$1T in treasuries to rebuild its TGA and most of them will come in the form of T-bills.

But that is still not the end. We still have another question unanswered. Why do MMFs want to rotate capital out of RRP into Bills?

Well, the answer is pretty simple, it is essentially the search of higher yields. One can think of the RRP facility as an alternative investment for a broad base of money market investors that offers interest (will explore in further pieces).

We currently have over US$2T sitting in RRP that yields 5.05%

Fig 10: ON RRP Agreements (FRBNY)

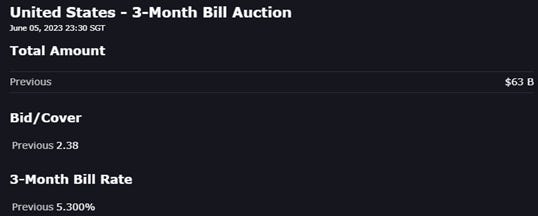

Fig 11: 3-Month T-Bill auctions (IBKR)

As one can see, the bill rate is higher than the current RRP rate, this incentivizes MMFs to rotate from the RRP into bills.

I know that some macro minds out here may ask if the rate is higher, why hasn’t the rotation already occurred? Well other than the issuance sizing aka not enough supply. The RRP facility serves another function too, it has to do with demand for collateral (i.e. USTs), which is in itself another rabbit hole to delve into (will explore in future pieces).

In summary, there’s nuances surrounding the rebuilding of the TGA post-debt ceiling deal. Whether bank reserves would be drawn out of the banking system is still dependent on the actions of the MMFs and different actors.

The award rate on O/N RRPs is 5.30% for $1,574.065 on 9/1/23. The rate on 3mo T-bills is higher. Thus, funds have come out of the O/N RRP.

There’s been a $734b drawdown since 4/24. That’s not a liability swap (removing cash from the FED). If that’s what it takes to fund the Treasury’s tsunami, then interest rates would have risen further without that funding source?